Planet Mercury as seen from the MESSENGER spacecraft in 2008. Image Credit: NASA

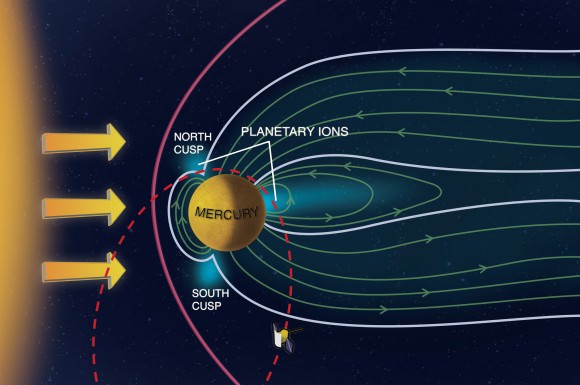

According to data from the The Fast Imaging Plasma Spectrometer (FIPS) onboard NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft, the solar wind is “sandblasting” the surface of Mercury at its polar regions.

Based on findings from one of seven different papers from the MESSENGER mission to be published in the Sept. 30th edition of Science, sodium and oxygen particles are charged in a manner similar to Earth’s own Aurora Borealis.

How are the University of Michigan researchers able to detect and study this phenomenon?

Using the FISP, the scientists at the University of Michigan have taken measurements of Mercury’s exosphere and magnetosphere. The data collected has provided researchers with a better understanding of interactions between Mercury and our Sun. FIPS data has also confirmed theories regarding the composition and source of particles in Mercury’s space environment.

“We had previously observed neutral sodium from ground observations, but up close we’ve discovered that charged sodium particles are concentrated near Mercury’s polar regions where they are likely liberated by solar wind ion sputtering, effectively knocking sodium atoms off Mercury’s surface,” said FIPS project leader Thomas Zurbuchen (University of Michigan).

In a UM press release, Zurbuchen added, “We were able to observe the formation process of these ions, and it’s comparable to the manner by which auroras are generated in Earth’s atmosphere near polar regions.”

Given that Earth and Mercury are the only two magnetized planets in the inner solar system (Mars is believed to have had a magnetic field in its past), the solar wind is deflected around them. The solar wind has made recent news due to recent outbursts from the Sun causing visible aurorae, caused by the interaction of charged particles from the Sun and Earth’s relatively strong magnetosphere. While Mercury does have a magnetosphere, compared to Earth’s it is relatively weak. Given Mercury’s weak magnetosphere and close proximity to the Sun, the effects of the solar wind have a more profound effect.

The Fast Imaging Plasma Spectrometer on board MESSENGER has found that the solar wind is able to bear down on Mercury enough to blast particles from its surface into its wispy atmosphere.

Image Credit: Shannon Kohlitz, Media Academica, LLC

Image Credit: Shannon Kohlitz, Media Academica, LLC

“Our results tell us is that Mercury’s weak magnetosphere provides very little protection of the planet from the solar wind,” Zurbuchen said.

Jim Raines, FIPS operations engineer (University of Michigan) added, “We’re trying to understand how the sun, the grand-daddy of all that is life, interacts with the planets. It is Earth’s magnetosphere that keeps our atmosphere from being stripped away. And that makes it vital to the existence of life on our planet.”

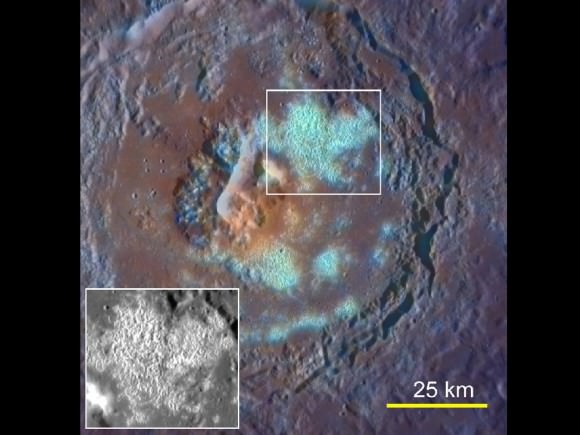

A high-resolution monochrome image has been combined with a lower-resolution enhanced-color image. The hollows appear in cyan, a result of their high reflectance and bluish color relative to other parts of the planet. The large pit in the center of the crater may be a volcanic vent, from which the orange material erupted. Credit: Courtesy of Science/AAAS

The MESSENGER team also released other results from the mission, including new evidence that flood volcanism has been widespread on Mercury, the first close-up views of Mercury’s “hollows,” and the first direct measurements of the chemical composition of Mercury’s surface.

MESSENGER, as well the the Mariner 10 flyby mission saw unusual features on the floors and central mountain peaks of some impact craters which were very bright and have a blue color relative to other areas of Mercury. This type of feature is not seen on the Moon, and were nicknamed “hollows.”

Now, with the latest MESSENGER data, hollows have been found over a wide range of latitudes and longitudes, suggesting that they are fairly common across Mercury. Many of the depressions have bright interiors and halos.

“To the surprise of the science team, it turns out that the bright areas are composed of small, shallow, irregularly shaped depressions that are often found in clusters,” says David Blewett, a staff scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md., and lead author of one of the Science reports. “The science team adopted the term ‘hollows’ for these features to distinguish them from other types of pits seen on Mercury.”

Blewett added the hollows detected so far have a fresh appearance and have not accumulated small impact craters, indicating that they are relatively young.

If you’d like to learn more about the MESSENGER mission, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/messenger/main/index.html or http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/

Sources: MESSENGER News Release NASA

Source: Universe Today

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario